Connecting Costa Rica to the World

CONNECTING COSTA RICA TO THE WORLD

European colonization of Costa Rica began in 1502 when, on his final voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus landed near present-day Puerto Limón to repair his hurricane-damaged ship. The local people welcomed him and brought him gifts of gold. Columbus claimed that he saw more gold in those few days than in all the time he had spent on Hispaniola (Española). Despite this, with more promising areas to explore and difficulties with hostile indigenous people and disease, it was not until 1561 that Spain's Juan de Cavallón led the first successful attempt to colonize Costa Rica. The Spanish crown established the village of Cartago in the Central Valley as its first permanent settlement in 1564.

TIMELINE

1502 – Christopher Columbus lands near present-day Puerto Limón to repair his ship

1502 – The region is inhabited by approximately 400,000 indigenous people

1561 – Juan de Cavallon leads first successful attempt to colonize the country

1564 – Spanish crown establishes the village of Cartago as first permanent settlement in Costa Rica

1564-1821 – Costa Rica is loosely governed by the Spanish Captaincy General of Guatemala

1710 – Disease and oppression have reduced the indigenous population to about 8,000 people

1808 – Coffee is introduced into Costa Rica from Cuba and becomes the principal crop

Costa Rica was a relatively impoverished and unimportant part of the Spanish Empire governed loosely by the Captaincy General of Guatemala. The colonial system was harsh and brutal, and it is estimated that, primarily because of disease, the indigenous population had declined to around 8,000 by the early 1700s. Although slaves were brought to Costa Rica in the 1500s, the lack of plantations and absence of extensive mining meant that most were employed as domestic servants. Unlike other parts of the Spanish colonies, large landholdings and plantations never developed in Costa Rica.

COFFEE

Coffee was first introduced into Costa Rica from Cuba in 1808 and soon became the major crop in the country. In many ways, coffee was a perfect crop for the region. Not suited for cultivation on large estates, it was adopted by the small landholders as a valuable cash crop. The historical and current importance of coffee was recognized in 2020 with a law declaring the product as a national symbol because of its role in the economic, social, and cultural development of the country.

Costa Rica’s economy during most of the 19th century was dominated by the cultivation of coffee. Introduced into the country from Cuba, by the 1820s coffee was the principal export crop. Coffee was grown in and around the country’s Central Plateau and when the road to the Pacific port of Puntarenas was completed in 1846, oxcarts were used to transport the crop for export.

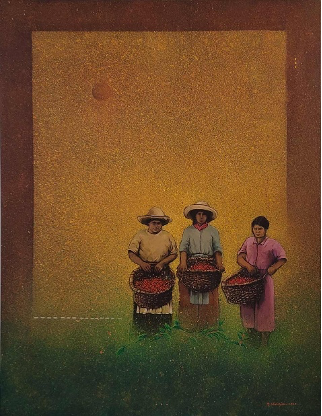

Coffee Pickers #14

Marité Vidales

Acrylic and Collage on Canvas

2020

Image from Marite Vidales and Pablo Zuniga

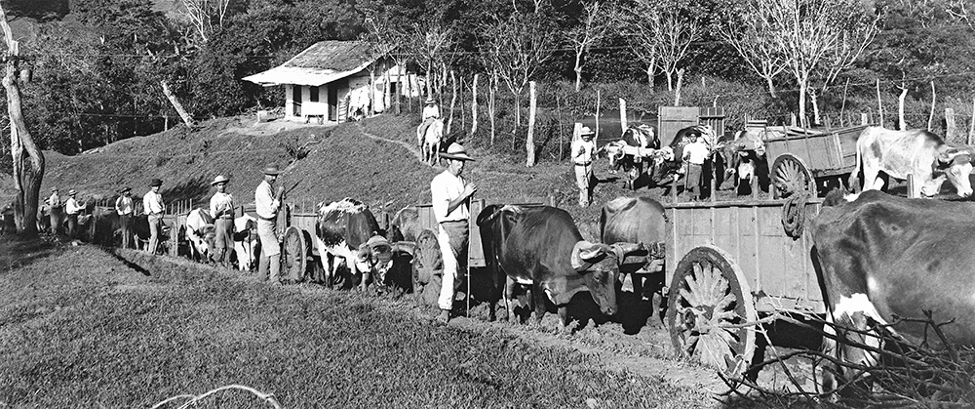

Weeding a coffee plantation in the late 1800s

Courtesy of the Ethnographic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

Collection: C.V. Hartmann

THE OXCART AND COFFEE

Because of their economic importance beginning in the middle of the 19th century, oxcarts have become one of the most iconic symbols of Costa Rica. By the early 1900s, people began painting and decorating their oxcarts (La Carreta) with elaborate designs. Different regions of the country adopted their own colors and designs to make identification easier.

Although the oxcarts were replaced by more modern means of transportation after World War I, the Carreta was designated the National Labor Symbol for Costa Rica in 1988 and declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO in 2005. Some farmers still use oxcarts during harvest season, but their main use today is for festivals, parades, celebrations, and adornments in restaurants and public spaces.

Ox Cart Wheel

Ricardo Solis

Acrylic on recycled materials

Loan from Ricardo Solis

One indication of the prosperity brought by coffee is the National Theater of Costa Rica that opened to the public in San José on October 21, 1897. Built at a time when the city’s population was less than 20,000, it is the finest historical building in the capital. It has been declared a national symbol of historical architectural heritage and cultural freedom and continues to present world-class performances.

Allegory of Coffee and Bananas Mural from the Ceiling of the National Theater

The most famous, and perhaps most controversial painting in Costa Rica is on the ceiling of the National Theater. Painted by the Italian artist Aleardo Villa who never visited the country, it is commonly known as “The Allegory of Coffee and Bananas.” Supposedly a composite of typical scenes in Costa Rica, there are several inaccuracies, which include coffee growing at sea level rather than in the mountains and upside down bananas.

Allegory of Coffee

Marité Vidales

Mixed Media

2019

Image usage from Marité Vidales and Pablos Zuniga

(Detail based on Allegory of Coffee and Bananas Mural from the Ceiling of the National Theater including a 5 colones bill that has the National Theater painting on its reverse)

Folding Chair and Stool

Leather and Wood

Costa Rica

Loan from Adriana Jimenez

US IMPERIALISM AND COSTA RICA

Costa Rica played a significant role in opposing the United States' imperial ambitions during what is known as the Filibuster War. As the U.S. expanded westward through the annexation of Texas and territories acquired in the Mexican-American War, the belief in "manifest destiny"—the idea that the U.S. was meant to dominate all of North America—became increasingly widespread.

William Walker was a journalist from San Francisco who raised an army to invade Central America. These so-called filibusterers, a term originally referring to unauthorized military expeditions, aligned themselves with a faction in Nicaragua's civil war, leading to Walker becoming president in 1856. Later that year, when Walker invaded Costa Rica, the factions in Nicaragua formed an alliance with Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala to defeat him. Following the destructive Filibuster War, Walker was expelled from the region.

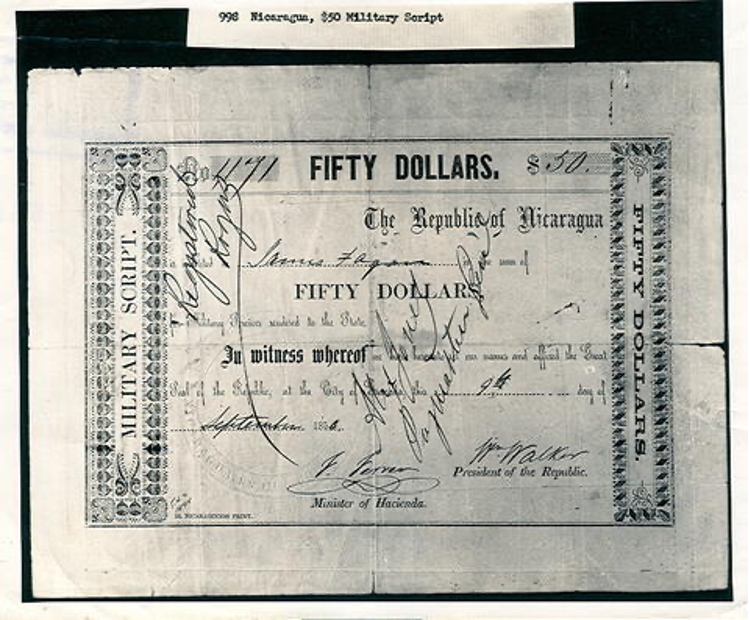

Photograph of one of the bonds issued in Nicaragua by William Walker to finance his military ventures in Central America. Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica CR-AN-AH-FO-000660-1-000660-2.

To commemorate the victory over Walker, Costa Rica erected a statue in 1895 in downtown San Jose. In what is now the National Park, the statue in the center depicts five women representing the five Central American countries that allied to fight two men who represent Walker and the filibusters. Juan Santamaría Rodríguez is celebrated as a national hero in Costa Rica for his actions in the 1856 Battle of Rivas during the Filibuster War. A drummer in the army, he died in the battle when he used a torch to light the enemy stronghold on fire. This helped secure the victory over Wiliam Walker and his forces. The victory over Walker eventually led to elections in Costa Rica in 1869, which began a democratic tradition that is distinct from its neighboring countries.

A statue of Juan Santamaría Rodríguez is installed in his hometown of Alajuela and the main airport of Costa Rica is named for him.

The term “Latin America” first came into usage around 1856 by Central and South Americans who were concerned with US expansion.

The idea was to differentiate the countries speaking languages with Latin roots from Anglo America. In the 1860s, the term Latin America was picked up by French imperialists to justify their occupation of Mexico and the region has been known by this term ever since.

THE RAILROAD AND BANANAS

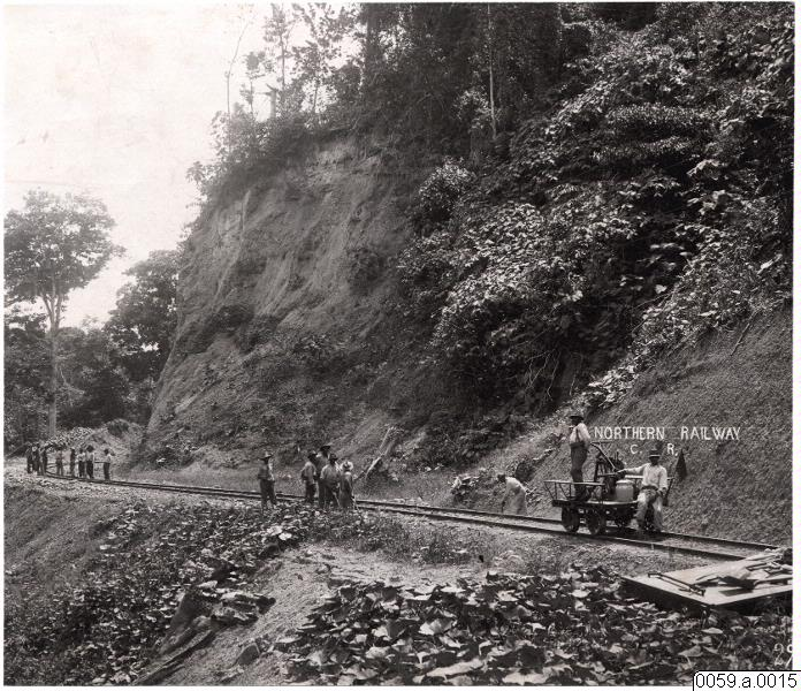

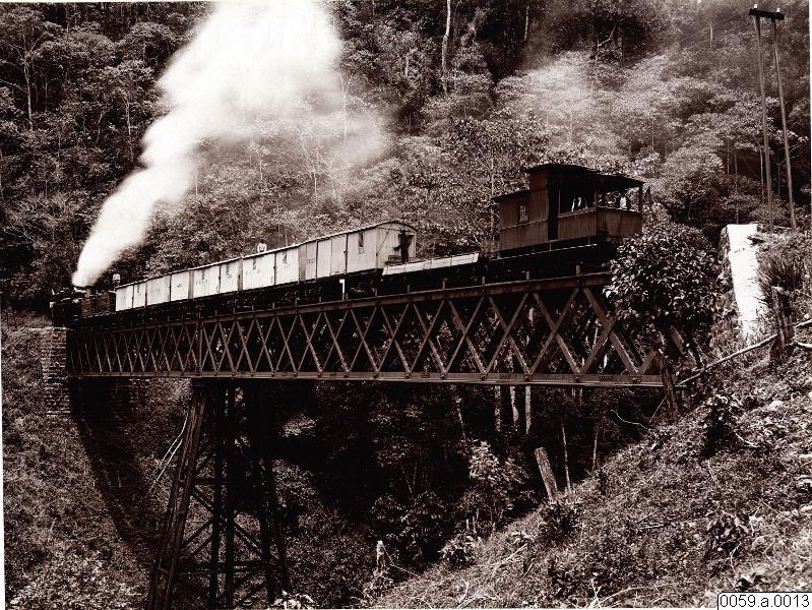

In the 1870s, the government recognized that building and expanding export markets required constructing a railroad to the Caribbean, so they contracted with US businessman Minor Keith to build track from San José to Limón. With great effort they overcame major problems of construction in difficult terrain, disease that affected the workers, and project financing, and the railroad was completed in 1890.

Large tracts of land (800,000 acres) along the train route were granted by the government to Minor Keith. Keith began cultivating bananas as a cheap source of food for his workers and, anxious to recoup some of his investment, he began exporting bananas to the US. By 1899, his business was incorporated into the United Fruit Company, for which he served as Vice President.

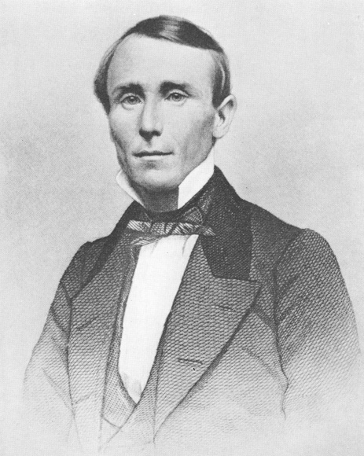

Photo of Minor Keith in 1917

Photo of Minor Keith in 1917

Many workers from Jamaica and other islands in the West Indies were recruited to build the railroad in Costa Rica and to work on the banana plantations along the Caribbean coast. Although important to the economy, these people and their descendants faced significant discrimination. For example, a contract signed between the United Fruit Company and the government in 1934 prohibited the company from employing “colored people” on its plantations on the Pacific Coast. It was not until 1949 that this prohibition was lifted and Afro-Costa Ricans became full citizens

The construction of the railroad in Costa Rica also played a huge part in creating collections of artifacts of the pre-Colonial past of the country. Keith kept many workers excavating ancient sites along the path of the railroad, uncovering pottery, jade, gold, and stone objects. Many eventually found their way into the collections of prominent museums in the United States including the Museum of the American Indian-Heye Foundation in New York. Minor Keith was a founding trustee of the Heye Foundation in 1916.

Marité Vidales

Plantains

1993

Acrylic on canvas

Loan from Marité Vidales and Pablo Zúñiga

Construction of the railroad to the Atlantic, Northern Railway Company

Courtesy of the Ethnographic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

Collection: C.V. Hartmann

Railway bridge on the Atlantic slope. Collected by C.V. Hartman 1897-99.

Courtesy of the Ethnographic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

Collection: C.V. Hartmann

Railway through a banana plantation, Northern Railway, Collected by C.V. Hartman 1897-99.

Courtesy of the Ethnographic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

Collection: C.V. Hartmann

Banana plantation on the Atlantic coast; teams of Jamaican laborers 1897.

Courtesy of the Ethnographic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden

Collection: C.V. Hartmann

The United Fruit Company transformed the economy of Costa Rica; by 1905 bananas were a commodity as valuable as coffee. Estimates are that by 1950, the company owned nearly 9% of the national territory, employed about 7% of the total labor force, and was responsible for 58% of the country’s exports.

By 1984, however, a hurricane that devastated its plantations in Honduras and a series of corruption scandals led the company to divest its landholdings and production capabilities and change its focus to marketing of bananas (now known as Chiquita Brands International).

- POLITICAL EVOLUTION OF COSTA RICA

TIMELINE

1821 – Becomes part of the independent Mexican Empire

1823 – Joins the Federal Republic of Central America

1824-25 – Province of Guanacaste secedes from Nicaragua and joins Costa Rica

1838 – Costa Rica declares independence

1848 Costa Rica adopts Constitution that establishes the First Costa Rican Republic

1855-1856 – American William Walker lands in Nicaragua mercenary army (filibusters), proclaims himself president, and invades Costa Rica

1857 – Costa Rica and Central American allies defeat Walker in the Filibuster War

1860 – Bananas introduced to Costa Rica from the Cayman Islands

1870-90 -– Costa Rica encourages intensive foreign investment in railways

1872 – US businessman Minor Cooper Keith promotes banana cultivation in Costa Rica to feed railway workers

1899 – United Fruit Company is formed

1905 – Bananas become as important to the economy as coffee

1917-1919 – Coup brings brief military dictatorship to power

1934 – Great Banana Strike leads to signing of a collective agreement with workers in 1938

1948 – Six-week civil war over a disputed presidential election result

1949 – New Constitution adopted

1987 – Leaders of Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras sign peace plan to end their civil wars

1987 – Costa Rican President Oscar Arias Sánchez awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for brokering the peace plan

When Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, Costa Rica was swept along in the independence movement of the other Spanish Colonies. Costa Rica became part of the independent Mexican Empire in 1821, and by 1823, it became part of the Federal Republic of Central America. Costa Rica declared its independence in 1838.

The Torch of Independence has been adopted as a national symbol of freedom in Costa Rica. The country celebrates Independence Day on September 15th, the date in 1821 when leaders in Guatemala City declared freedom from Spain. It took many months for that news to reach Costa Rica. To commemorate this, each year students carry the torch through the countryside to reach Cartago, the former national capital, by September 15.

Photo from Tico Times, 2021. Photo from Tico Times, 2021. |

Costa Rica had minimal interaction with the Federal Republic of Central America and in 1838 formally declared its independence. By 1848, under the leadership of President José María Castro Madriz, officially the “Father of the Country,” a reformed constitution was adopted that included support of freedom of the press, secularism, and civil rights. Twice elected President, the period he began is referred to as the First Costa Rican Republic that lasted until 1948.

José María Castro Madriz (1818-1892) was the first and fifth President of Costa Rica

At the turn of the twentieth century, Costa Rica was a small player on the world scene. With a small group of surviving indigenous people, a small population of Jamaican and Chinese people, and descendants of Spanish colonists, the country’s population remained under 50,000. Apart from the railroad from San José to Limon, infrastructure remained severely underdeveloped.

Modern Costa Rica was shaped by a 44-day Civil War that erupted after a disputed presidential election in 1948. A rebellion against former president Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia who tried to return to power was led by José Figueres Ferrer, Figueres’ rebels quickly defeated the ill-equipped Costa Rican army and militias of the Communist People’s Vanguard Party. It is estimated that about 2000 people were killed during the Civil War, the bloodiest event in the 20th century in Costa Rica.

José Figueres Ferrer is a national hero in Costa Rica. A successful coffee farmer and rope manufacturer, he was forced into exile in Mexico in 1942 after publicly criticizing President Calderón. Following the Civil War, Figueres became the de facto leader of Costa Rica, and was again elected president from 1953 to 1958 and from 1970 to 1974. His son, José Maria Figueres, also served as president from 1994 to 1998.

Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia remains controversial in Costa Rica.

He was a medical doctor who continued to practice surgery while serving as president. Coffee growers supported his election in 1940, but he quickly went against their interests by enacting a tax system based on ability to pay, introducing a minimum wage, combatting poverty, and improving health conditions for the poor. His attempt to overturn the results of the election and return to the presidency, however, led to the Civil War in 1948. Calderón fled to exile in Mexico but was allowed to return in 1958.

Figueres and his supporters laid the foundation of what makes Costa Rica unique today by abolishing the army and enacting many social reforms. The army was replaced by a small national police force, public education for all was guaranteed, women and illiterates were given voting rights, citizenship was granted to the children of black immigrants, a civil service system was established, and a public welfare system to guarantee basic nutrition and health care to everyone was created. The National Liberation Party (Partido Liberación Nacional) they created continues as a major political force in Costa Rica and follows the ideology of democratic socialism.

Monument to José Figueres Ferrer commemorating his abolishing of Costa Rica's army in 1948, Plaza de la Democracia

Photo by Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz, 2019.

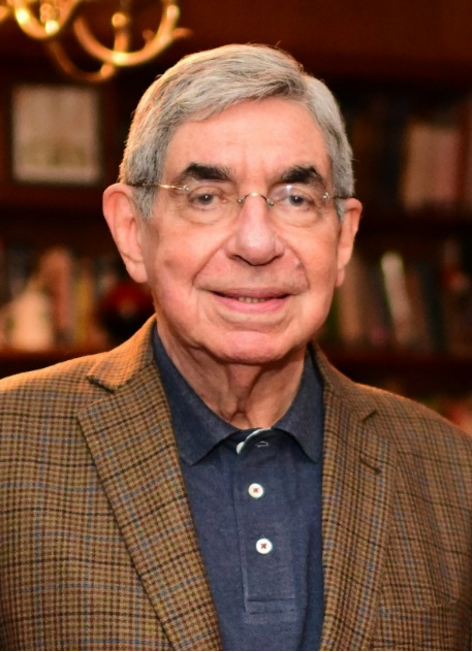

After 1948, Costa Rica did not experience the numerous civil wars, revolutions, and political upheavals that plagued its neighbors in the 1970s and 1980s. Bred from stark inequalities and poverty, these crises afflicted Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama. Costa Rican politicians were leaders in efforts to end the civil wars in Central America, which culminated in a Peace Plan signed by the presidents of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica in 1987. The accord established a framework for peaceful conflict resolution and economic cooperation. For his role in brokering this agreement, Costa Rican president Óscar Arias Sánchez was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987.

Video link:

A Bold Peace: Costa Rica's Path of Demilitarization (2016) Full Documentary

Photograph from Wikimedia Commons Photograph from Wikimedia Commons |

Óscar Arias Sánchez, former president of Costa Rica 1986-1990 and 2006-2010.

Photograph taken from the website of the Municipality of Desamparados. Photograph taken from the website of the Municipality of Desamparados. |

Laura Chinchilla Miranda is the only woman to be elected president of Costa Rica. A member of the National Liberation Party, she served from 2010-2014. She was the eighth woman to serve as president of a Latin American country.