Prehistory & Archaeology

COSTA RICA’S PREHISTORY

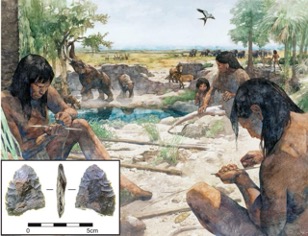

The prehistory of Costa Rica began when the first human inhabitants arrived in Costa Rica between 9,000 and 11,000 years ago. The early settlers were nomadic people who survived by gathering wild plant resources and hunting Ice Age animals such as giant armadillos, sloths, and mastodons. By about 5,000 BCE, with the extinction of these larger animals, the indigenous people began to rely more heavily on hunting smaller mammals like tapirs, collared peccary, and deer. With the end of the Ice Age, the warmer climate created an abundance of tropical vegetation including a greater variety of fruits and vegetables for harvesting. By circa 2,000 BCE, people began to farm tubers, corn and other plants, and cultivated fruit trees and palms. This allowed the development of permanent villages and the formation of more complex societies.

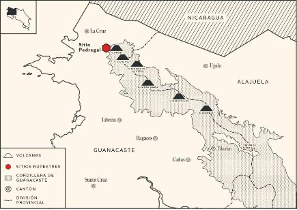

Archaeologists have generally divided Costa Rica into three zones whose cultures produced artifacts of distinctly different styles, especially after 500 CE.

Guanacaste/Nicoya on the Pacific Coast is a relatively dry region with distinct rainy and dry seasons. The Central Highlands/Atlantic Watershed is made up of many valleys, rivers, and extensive lowland plains along the Caribbean Sea. The Diquis zone in the southwest part of the country has intense rainfall and a wide diversity of flora and fauna but has relatively infertile soils.

TIMELINE

10,000-8,000 BCE – First human occupation by nomadic hunter/gatherers, use of stone tools

8,000–2,000 BCE – Shift to more diverse diets, creation of semi-permanent settlements, early pottery, and more diverse stone tools

2,000 BCE–300 CE – Maize, beans, squash agriculture, development of villages, more elaborate pottery, influences from Mesoamerican cultures

300–800 CE – Chiefdoms (hierarchical societies) develop, increased trade networks with Mesoamerica and northern South America, metallurgy begins, stone spheres appear in southern region (Diquis)

800–1500 CE – Development of complex chiefdoms and small cities, greater inequality in societies, more regional diversity of cultures.

Illustration by Greg Harlin Illustration by Greg Harlin |

Early inhabitants of what is present-day Costa Rica were nomadic hunter-gatherers. These early groups were likely small bands of 20-30 people related by kinship. Moving frequently, they hunted animals and gathered plantlife to sustains themselves.

The 300 stone spheres of Costa Rica are found on the Diquís Delta and on Isla del Cano. Locally, they are also known as bolas de piedra (meaning “stone balls”). The spheres are commonly attributed to the extinct Diquís culture, and they are sometimes referred to as the Diquis spheres. They are the best-known stone sculptures of the Isthmo-Colombian area.

By 300 BCE, larger settlements began to appear with more specialization of labor. Chiefs or elites with centralized power are in evidence. While the remains of plazas, fountains, temples, stone mounds, and tombs have been found, these indigenous people never developed the walled buildings, pyramids, and complex societies that the people of the Andes or of Middle America had at the time. Evidence does, however, indicate that people inhabiting what we now know as Costa Rica had contacts and trade relationships with those more advanced cultures.

After 800 CE, Costa Rican society became more stratified with more monumental architecture, a greater prevalence of polychrome pottery, and the use of gold as ornamentation for more powerful people in society. Pottery especially in northern Costa Rica shows greater influence of ceramic traditions from central Mexico and the Maya. Gold objects begin to appear in burials and jade objects virtually disappear.

Photo by Marunde Photo by Marunde |

Guayabo National Monument

Located on the southern slope of Turrialba Volcano, this national monument was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2009. It is the site of a city that was inhabited from about 400-1400 CE and may have been home to as many as 2,000 people. Its buildings, aqueducts, roads, and bridges suggest it was home to an advanced society.

During the period from 1000 CE to 1550 CE, indigenous people in Costa Rica were largely organized into chiefdoms whose leaders had both political and religious authority. The people participated in extensive trade networks for objects like jade, gold, and ceramics. Exquisitely carved metates disappear. Pendants, bracelets, headbands and other gold objects appear, stone human figures are produced, and pottery with increasingly ornate and elaborate designs becomes common. It is estimated that at the time of Spanish arrival the population numbered approximately 400,000.

Vasija inclinada (Inclined Vessel)

Marité Vidales

Oil on Canvas

Costa Rica

1989

On Loan from Marité Vidales

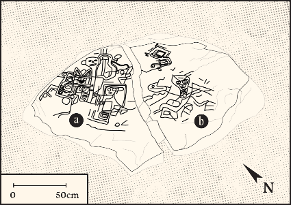

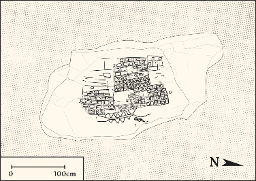

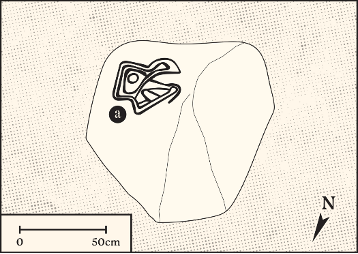

Petroglyphs in Costa Rica

Petroglyphs (prehistoric rock carvings) have been found in many different regions of Costa Rica. A recent French/German/Costa Rican collaborative project identified and studied 74 archaeological sites with the Guanacaste Volcanic Mountain Range in the northwestern part of the country. Approximately 277 rocks were identified with geometric, zoomorphic (fish, lizards, birds), and anthropomorphic figures. These petroglyphs have been associated with burial and habitation sites of people who lived in the region between 500 BCE and 1500 CE.

“A Past Between Lines: Rock Art Manifestations” presented the results of this research in a temporary exhibition at the Museos Banco Central de Costa Rica, which is available online at: Exhibición – Un pasado entre líneas

The Pedregal Site on the slopes of the Orosí Volcano near the border with Nicaragua have some of the most spectacular and better preserved of these petroglyphs. There are approximately 200 rocks in this area with carvings.

|

|

|

Possibly a representation of a shaman.

|

|

|

Zoomorphic representations

|

|

|

Geometric designs

|

|

|

Likely a representation of a Harpy Eagle head.

|

|

Pre-Columbian Pottery

Marité Vidales

Oil on Canvas

Costa Rica

1989

On Loan from Marité Vidales

CERAMICS

Miniature Objects

Ocarinas are small ceramic musical instruments that have been commonly found in burials. The earliest examples that have been found date to approximately 2500 BCE. Ocarinas played a significant role in rituals and ceremonies. Ocarinas of many designs have been found including birds, turtles, and mammals.

Ocarina in the Form of an Armadillo

Guanacaste/Nicoya

300-500 CE

Ceramic

Carl V. Hartman

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2793.55

Ocarina with Woman Holding a Baby Sitting on a Metate

Guanacaste/Nicoya (Las Huacas)

300-500 CE

Ceramic

Carl V. Hartman

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2793.19

Polychrome Figurine of a Woman

Guanacaste/Nicoya

800-1300 CE

Ceramic

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2438.2043

|

|

|

Polychrome Effigy Vase with Arms Holding a Jaguar Head

Ceramic

Guanacaste/Nicoya (Probably made in Nicaragua and traded to Guanacaste)

800-1300 CE

Estate of Juan Troyo

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2438.1443

Tripod Smoked Bowl with Monkey Representation in Relief

Ceramic

Costa Rica

800-1200 CE

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2939.3655

Ornately Decorated Three-Legged Vessel

Ceramic

Central Highlands/Atlantic Watershed (Irazu Area, Chinchilla Site)

500-800 CE

Carl V. Hartman

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2793.2332

Polychrome Tripod Bowl with Turtle Head

Ceramic

Guanacaste/Nicoya

800-1300 CE

Estate of Juan Troyo Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2439.32

Polychrome Tripod Bowl with Clay Balls Inside Legs

Ceramic

Costa Rica

800-1550 CE

Carl V. Hartman

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2793.99999mm

Effigy Bowl with Feline Figure

Ceramic

Guanacaste/Nicoya

800-1300 CE

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2438.1417

Polychrome Boat-Shaped Vessel

Ceramic

Costa Rica

1000-1300 CE

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2438.1486

Tripod vessel with 2 human faces

Ceramic

1000-1550 CE

Likely Central Highlands/Atlantic Watershed

Estate of Juan Troyo Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2439.534

Stone Objects

Some of the most impressive objects from Costa Ruca are beautiful carved stone metates found in burials along with offerings of jade and maces. Metates were and are undecorated common kitchen tools used for grinding corn. Ceremonial metates of volcanic basalt that are found in burials of high-status individuals are often carved with the heads and bodies of birds, reptiles, and mammals. Some people think they were intended to be throne-like seats or biers for deceased leaders although a mass burial from Las Huacas in Guanacaste included fourteen metates!

The stonework that was accomplished by indigenous peoples in Costa Rica is particularly impressive because of the lack of metal tools to shape the objects. After 1000CE, fewer metates were produced but stone stools, warrior figures (some holding trophy heads), and humans appearing to be playing flutes were produced.

Diquís Sphere

Stone

Diquís

Date unknown

Loan from Ghisselle Blanco

Figure with Hat Holding Trophy Head in One Hand, an Axe in the Other

Central Highlands/Atlantic Watershed

Likely 1100-1550 CE

Stone

Estate of Juan Troyo Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2439.2952

Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) Club Head

Guanacaste/Nicoya

300-500 CE

Stone

C.V. Hartman Excavation

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 12769-66

Photo by ChepeNicoli Photo by ChepeNicoli |

Harpy Eagle with its prey

Metate with Harpy Eagle Head

Guanacaste/Nicoya

300-600 CE

Stone

El Presbytero José M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2438.1406

Tetrapod Metate with Jaguar Head

Central Highlands/Atlantic Watershed (Chinchilla Site, Cartago)

500-1550 CE

Stone

Carl V. Hartman

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2793.2076

Human Figure with Hands on Chest

Likely Central Highlands/Atlantic Watershed

1100-1400 CE

Stone

Estate of Juan Troyo Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2439.2959

CELTS AND AMULETS

Among the most common artifacts from Las Huacas and other archaeological sites are celtiform pendants. Celts, often described as greenstone axe heads, were first created by the Olmec people of the Gulf Coast after 1000 BCE. For the Olmec and the people of Las Huacas, these celts primarily were used as adornments for high status people. The greenstone celts from Las Huacas and other Costa Rican sites are often drilled with a hole so that they can be worn as a pendant. Celts were sometimes transformed into avian or anthropomorphic characters or skillfully carved with these motifs.

Celtiform Pendant

Guanacaste/Nicoya

300-600 CE

Jadeite

On Loan from Joel Aaronson and Claire Keyes

Celtiform Pendant

Guanacaste/Nicoya

1-500 CE

Jadeite

On Loan from Joel Aaronson and Claire Keyes

Incised Bat with Spread Wings Amulet

Guanacaste/Nicoya

300-600 CE

Stone

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2939.1181

Amulet with Quetzal Representation

Guanacaste/Nicoya (Las Huacas)

300 BCE-300CE

Stone

C.V. Hartman Excavation

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2793-95

A resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno)

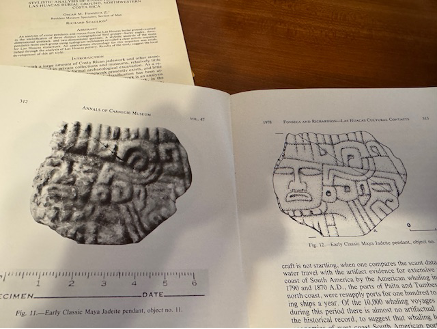

Artifacts Showing Linkages with South America and the Maya Area

Recent analysis of the CMNH collection by Costa Rican and American archaeologists has identified objects that reflect cultural contacts with both the Maya region and with South America. Illustrations on Moche (a Peruvian culture) pots from between 100 to 800 CE, ethnohistorical descriptions of these from the 16th century, and other evidence has suggested that balsa rafts may have been the means of transportation used by the Maya civilizations in Middle America and civilizations in South America to trade with each other. The artifacts from Las Huacas indicate that they were likely a part of this network of trade and cultural exchange.

Camelid

Steatite

Guanacaste/Nicoya (Las Huacas)

300-600 CE

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2939.1273

These camelid representations are one piece of evidence for cultural connections between Costa Rican cultures and South America. Camelids (e.g. llamas, vicuna, alpaca) are animals only found in South America at high altitude and arid environments.

This face pendant is one of 12 artifacts from Las Huacas that have been interpreted as having Mayan influence.

Jadeite Pendant

Guanacaste/Nicoya (Las Huacas) Trade from Maya

250-650 CE

El Presbytero Jose M. Velasco Collection

Carnegie Museum of Natural History 2939.1628

This fragment seems to be representing a power figure because of the presence of ear ornaments and what appears to be a necklace.

GOLD

Metallurgy in the Andes of South America began as early as 1400 BCE but gold does not appear in Costa Rica until several centuries later. The earliest gold objects in Costa Rica were probably introduced from Colombia between 0 and 500 CE. After 800 CE, gold objects were increasingly used in burials of prominent individuals. Gold was never in abundance, coming from deposits in streams rather than mining. Some archaeologists speculate that the increasing prevalence of gold was associated with greater inequalities in the societies of the time.

Gold objects from Costa Rica often incorporate figures of the fauna that was found in the environments occupied by these indigenous peoples. Birds, turtles, bats, frogs, and many other life forms are represented, often merged with human figures. The Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica has nearly 700 gold objects on exhibit and in its collections. Some years ago, the Museum made replicas of some of the most important of these pieces so that they could be exhibited in locations such as our museum.

Bird Pendants

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Human/Bat Pendants

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Bell with Bird Figure

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Pendant with Glass Frog (genus Centrolidae)

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Pendant with Tree Frog

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Pendant with Tree Frog

Pendant with Tree Frog

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Pendants with Human Forms

Pacific Coast (Diquis)

700-1550 CE

Loan from Pre-Columbian Gold Museum of the Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica

Spotlight on Carl V. Hartmann

Some of the best evidence concerning the prehistory of people in Costa Rica resides in the collections made by Carl V. Hartman (1862-1941) that are now at Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) and the Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm, Sweden. Originally trained as a botanist in Sweden, Hartman turned his attention to anthropology and archaeology in the 1890s. In 1903, Hartmann was hired by the Carnegie Institute, which was then collecting objects to be exhibited in the museum newly founded by Andrew Carnegie. During his work for the Carnegie, he purchased existing collections and carried out archaeological excavations in several regions of Costa Rica. The results of his collecting and research were exhibited when Carnegie Museum opened to the public in 1907. Most of the objects on display here have not been seen by the public since the early 1900s.

The Research Work

Hartman’s research work, including at a site called Las Huacas on the Nicoya Peninsula, was unique in that it was one of the earliest excavations done using systematic grid methods now standard in archaeology. The excavations of Hartman at Las Huacas have established that the site was occupied during the period between 180-525 CE. At the time, this was a chiefdom level society with individuals specialized in producing different kinds of utilitarian and elite goods. Most of the artifacts found by Hartman were associated with burials. Although this collection was relatively neglected until the 1970s, because of the careful documentation done by Hartman, it has since been studied intensively by Costa Rican, American, and other archaeologists.

.

The Objects

In the objects that they created, the people of Las Huacas represented the birds, bats, turtles, amphibians, and felines that were important parts of their environment. The objects in the burials were not for everyday use but were markers of the social status of the deceased. The jade objects were likely the most highly valued items at the time and buried with the wealthiest and most powerful individuals and their families. Interestingly, jade objects in Costa Rica virtually disappear around 700 CE with gold objects becoming much more common.

C.V. Hartman in Costa Rica in 1903. Carnegie Museum of Natural History Section of Anthropology glass plate negative G960.

Photo courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. C. V. Hartmann archaeology/ 1900.

Playful and Colorful #5

Marité Vidales

Oil on canvas

2023

On loan from Marité Vidales